“On the eventful path,

the goal merges with infinity.”

— Li Shenfeng: A Collection of Treatises

This series of articles will discuss the development of a small desktop CNC milling machine, primarily intended for working with aluminum. For instance, I already have a 3D printer for plastics and a mid-size milling machine for wood. But when it comes to aluminum and other soft metals—I’ve got nothing.

That’s the official explanation. Realistically, at the start of the project, there weren’t any concrete plans for this machine. Then again, it’s widely known that appetite comes during a plague. We’ll see how it goes…

As with many of my projects, this one had a challenging journey and a rich backstory. That’s where I’ll begin, following the old tradition.

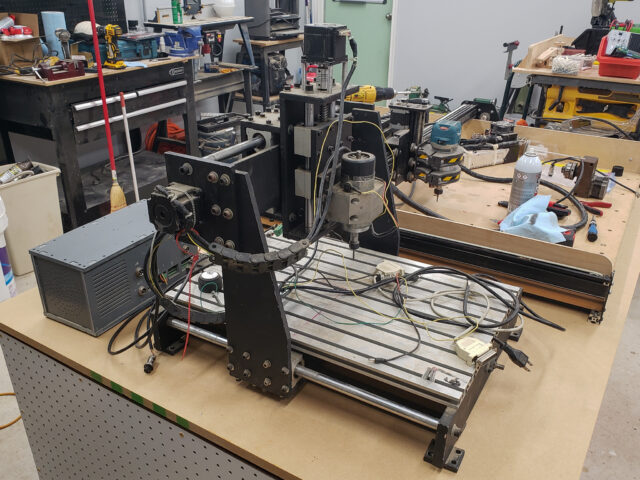

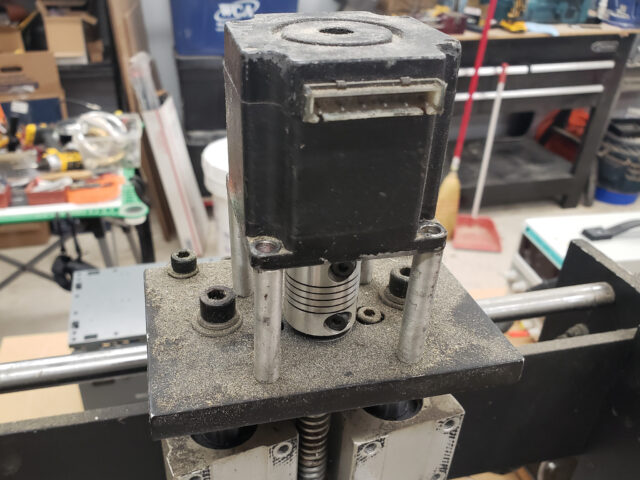

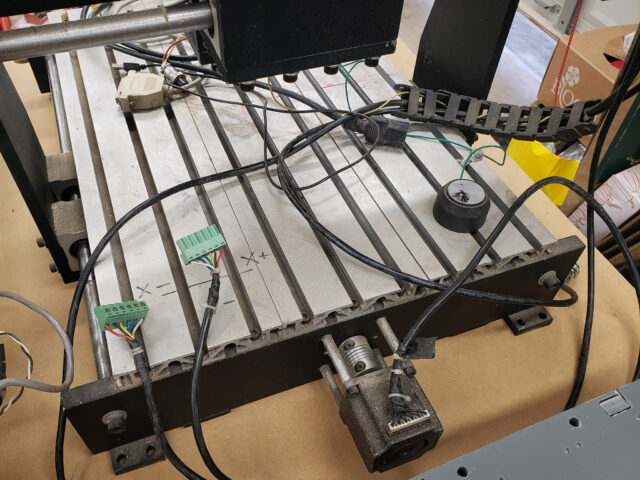

Unlike the 3D printer, which was designed and built completely from scratch, the milling machine already had some sort of pre-existing foundation. It looked like this:

Some might get the false impression that this isn’t just the “foundation” for the project but a fully functional machine. Clean it, oil it, turn it on, and you’re good to go… If only it were that simple…

Grab a mug of WD-40, wrap yourself in a cozy old oil-stained rag, sit close to the barrel of burning stools, and listen to the promised backstory about the difficult fate of this machine…

Long ago, when I first started working at a small company that manufactured and sold firearms (Texas Shooters Supply), this machine was already sitting in the corner of the workshop, covered in a thick layer of dust. Based on some indirect signs, its approximate year of origin can be placed between 2010 and 2013 (although the spindle motor is marked 1997 — I strongly doubt the rest is that ancient).

The boss explained that he had purchased it for what I would consider an outrageous amount of money — with direct delivery from China in the early 2010s — to support the company’s growing needs.

Even back then, I was convinced the poor guy had been tricked due to his lack of knowledge. First of all, it’s nowhere near suitable for industrial use — it’s a typical hobbyist toy. Secondly, even back then, the price for such toys hovered around $800 — no more.

In my memory, it was turned on only once. That was when the boss made another attempt to adapt it for engraving purposes.

Somehow, it managed to gouge out the company’s logos on aluminum parts. I even admit that it might have done this faster and better. But at that time, I was actively engaged in organizing the company’s IT infrastructure, so I had no time to tinker with some silly “production” equipment. When no notable results — from the perspective of actual “production” — were achieved, the boss sent the machine back to its dusty corner.

🕒 Time passed…

At some point, one of my colleagues at the time asked to borrow the machine for personal use. She and her husband wanted to set up a small garage operation for engraving small batches of random trinkets. Of course, they didn’t succeed either. Mainly because the machine’s condition by then could only be described as “ruins.” Any tool — especially a machine left unused for years, coated with dust and shavings, unprotected from moisture, and carelessly kicked from corner to corner — will inevitably turn into ruins.

The colleague herself was quite creative and skilled, but only in areas related to applied arts. She crafted beautiful small accessories, like intricate leather lace wraps for pistol grips, earrings made from shell casings, bullet pendants, and other such jewelry. Her creations were truly beautiful! Unfortunately, by that time, the machine needed a machinist — not a jewelry crafter.

In the end, after a summer tour to a Texas farm, the machine returned to its dusty corner in the workshop.

🕒 Time passed…

Nobody, including the boss, had any use for the machine (or rather, the ruins of its ruins) anymore. By that point, I had finished tidying up the company’s IT infrastructure and had moved on to the production side of things. I got the company’s three serious CNC machines up and running: two milling machines — Doosan and Brother, a Doosan lathe (the Lynx model), and a Swiss-type machine (I’m not sure what these are called in Russian) from Mitsubishi. Together, these more than covered the company’s production needs, churning out parts by the dozens or hundreds, 24/7, under the watchful eye of a trained machinist tasked with clearing the chips.

For engraving purposes, we had repurposed two industrial laser engravers from Epilog, which were far more suitable for the job.

I mention all this to illustrate just how laughable and absurd — from the company’s perspective — that dusty little hobbyist machine sitting in the workshop corner had become. At some point, it no longer even warranted passing glances.

Yes, personally, I saw some potential in it for my garage hobbies. But every time I thought about the sheer amount of effort and time it would take to bring it back to life…

🕒 Time passed…

Все рано или поздно заканчивается. Так подошло к концу и моё время работы в той компании. Споткнувшись в очередной раз о кучу костей в углу, решил – да и фигли, собственно? Другой возможности уже не будет… В свой последний рабочий день попросил босса подарить мне те останки. Ну, типа, “за заслуги перед отечеством”. Вместо золотых часов или, там, радиоприёмника… Ведь, все равно, не сегодня, так завтра, он сам же и отправит его в утиль, чтобы угол освободить под новый компрессор. Жалко ж зверушку, нельзя так…

И в тот же день руины перекочевали из пыльного угла оружейной мастерской в пыльный угол моего гаража.

🕒 Time passed…

Everything comes to an end eventually. So did my time at that company. Stumbling yet again over the pile of bones in the corner, I thought — why not? There wouldn’t be another chance anyway. On my last day at work, I asked the boss to give me those remains as a parting gift. Sort of a “thank you for your service” gesture. Instead of a gold watch or, say, a radio receiver… After all, sooner or later, he would have scrapped it himself to free up the corner for a new compressor. Poor thing — you can’t just let it go out like that…

And so, on that very day, the ruins moved from the dusty corner of the firearms workshop to the dusty corner of my garage.

🕒 Time passed…

The only one who, it seems, still remembered the dusty ruins in the corner was my Friend. To this day, I’m not entirely sure what specific plans he had for that machine, but unlike me, he constantly remembered it and regularly nagged me with the question, “So, when are we going to start making chips?!”

The entire time, I persistently tried to offload the ruins onto him, hoping he’d bring them back to life himself. But he turned out to be smarter than I’d thought and successfully dodged the offer. He understood just as well as I did that restoring this little beast with his own hands wouldn’t be a walk in the park. On the other hand, constantly nagging me about it — well, that’s much easier than lifting heavy loads.

🕐 Suddenly, the time is came!

Just like that, out of the blue, with no particular reason. One fine day, I simply decided, “It’s time!”… Perhaps the Voices in the Head figured this would be a good way to distract me from everything happening in the world.

And so, the project began. End of story.

Now, it seems fitting to dive deeper into the technical details of this machine and explain why I didn’t harbor any grand illusions about its potential.

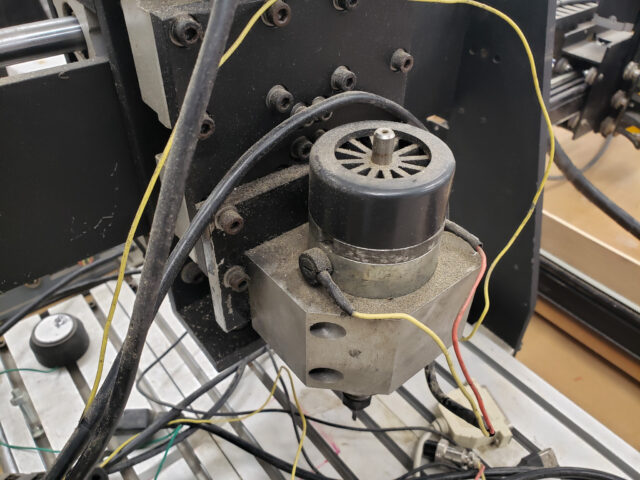

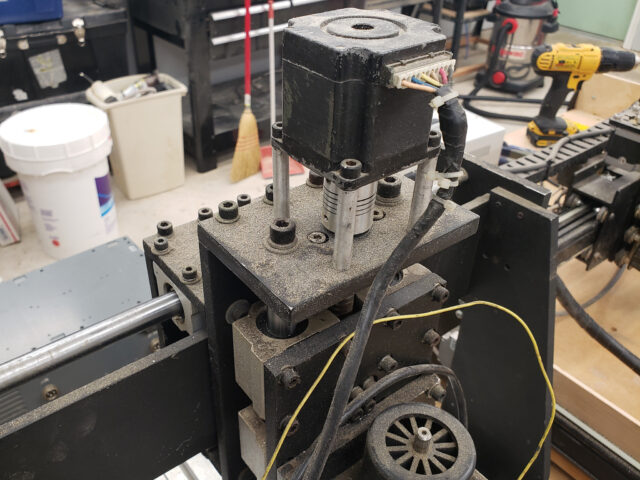

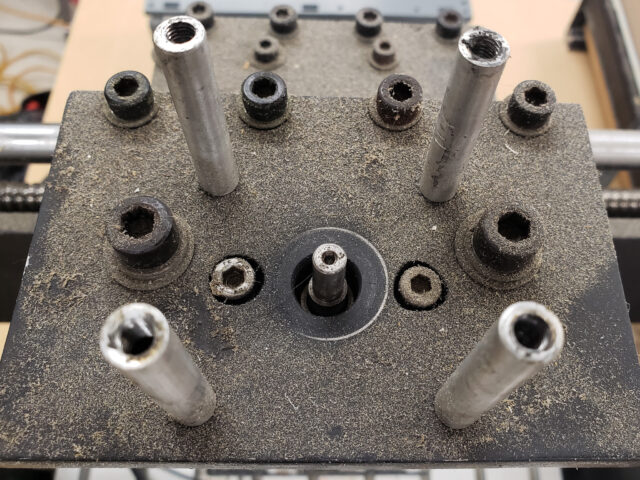

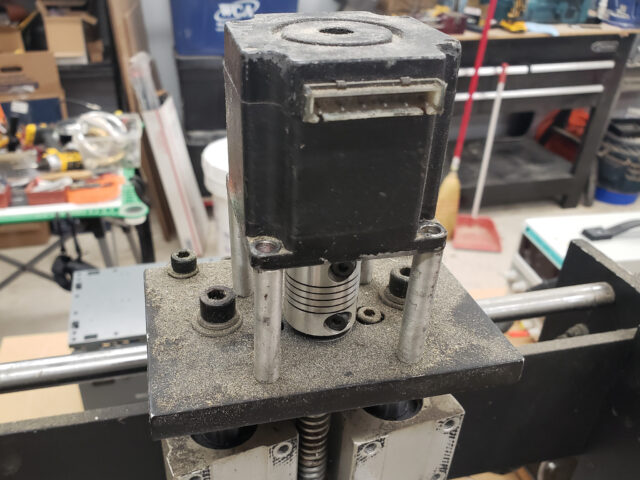

Technically speaking, there was absolutely nothing special about it. None at all! First and foremost, it really shouldn’t have been called a “milling machine” — even with qualifiers like “hobbyist,” “home,” or “for DIY projects.” Judging by its actual specifications, the machine was no more than a “mediocre hobbyist engraver.” As for being a “milling machine,” it severely lacked the power in its ancient stepper motors (the weakest variation from the ancestral NEMA23 series) and its spindle (10,000 RPM with 0.2 kW of power — basically, nothing to write home about).

You can find siblings and cousins of this machine in countless numbers on Alibaba, YouTube, and elsewhere online. While I couldn’t trace its origins to a definitive source, it seems that sometime in the mid-2000s, a DIY CNC project became widely available. Most likely, it circulated as detailed plans and blueprints distributed under a Creative Commons license. Back then, this was common — hobbyists would purchase these “papers” for a small fee and then cobble together something “inspired by” the project, improvising as much as their resources and creativity allowed.

Over time, this project spawned countless similar machines of all sizes and configurations, ranging from hobbyist-grade to commercial. Some were sold as ready-made products, others as kits. They’re still being produced today under a million different names and brands, alongside newer designs made from aluminum extrusion profiles (a trend that hasn’t done these machines any favors, by the way).

However, amidst this entire zoo of machines, you can clearly discern a “common ancestor.” This is evident just by looking at the design of some parts: the identical shape of the gantry’s uprights with their distinctive slanted edges, the solid rear panel, the questionable “end-to-end” assembly of structural elements, and so on:

What this ancestral project was exactly, I never definitively figured out. The trail led to China and then dissolved into millions of clones, manufactured over the last decade or so for a bowl of rice, a cat as a wife, and a boost to one’s social credit score. There’s a possibility that all of this is nothing more than a “metallic” iteration of the well-known DIYLILCNC project.

But I can’t state this with certainty. Much like the origin of humanity, this story has its own “missing link.” I couldn’t identify enough clear, historically traceable intermediate forms between DIYLILCNC and what you see in the photos above.

If anyone has genuine information about the ancestral project, feel free to share it in the comments or via email. I’d love to include a link — it’s always fascinating to trace the origins!

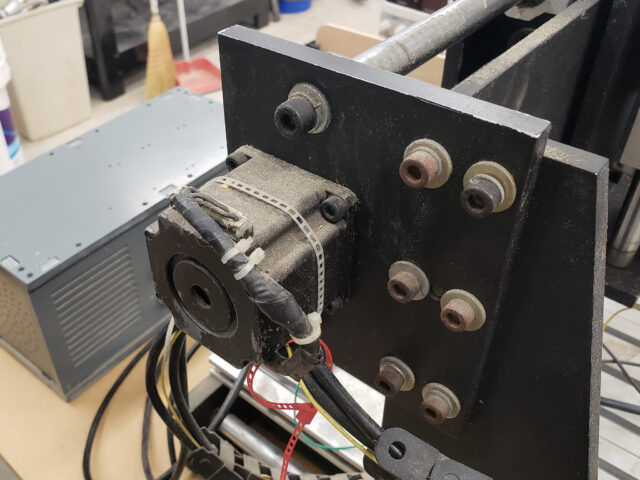

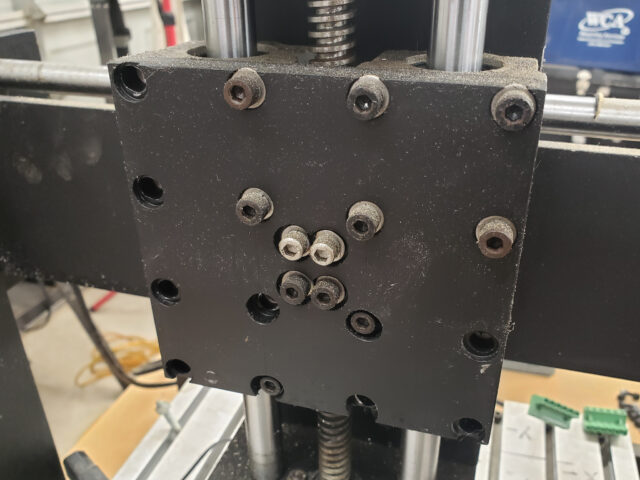

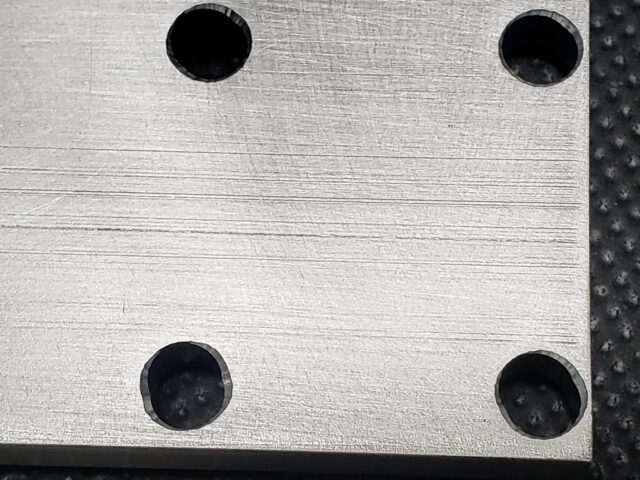

The machine that fell into my hands was most definitely not built from an industrial kit. Every single part bore unmistakable traces of handmade craftsmanship. And “made with love” — well, that definitely wasn’t the case here. The work was done hastily and carelessly, clearly intended for quick, one-off private sale during the hype wave.

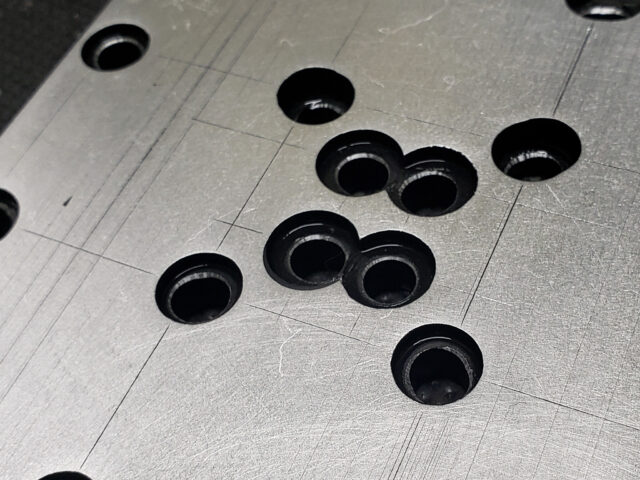

The parts still showed signs of manual scribing, like “calipers on the edge” markings — a dead giveaway of cottage-style, one-at-a-time production. Panels were cut manually, probably with a hacksaw, judging by the cut marks. Holes were drilled with a handheld screwdriver — not a single one was properly aligned, all skewed and off-mark, with obvious traces of subsequent adjustments.

Threads were either incompletely tapped or tapped at an angle. In one hole, I even found remnants of a broken tap. To make matters worse, a bolt for that hole had been shortened with a hacksaw so it could at least catch onto a couple of remaining threads. This is beyond inhumane — it should be illegal, in my opinion.

The post-processing? A very cheap aerosol paint job, like a “we painted a fence” vibe. The paint peeled off in flakes at the slightest scratch:

For some reason, they even painted the stepper motors! WHY PAINT MOTORS, CARL!?

Винты использовались в широком ассортименте. В основном M5 и M6. Даже в однотипные отверстия в пределах одного узла были вкручены винты разной длины. Зависело, вероятно, от того, насколько глубоко удавалось нарезать резьбу в детали. Под ту глубину и подбиралась длина винта…

The screws were a mix-and-match affair, primarily M5 and M6. Even within a single assembly, screws of different lengths were used — likely dictated by how deep they managed to tap the threads. The length of the screw was apparently chosen to match however much thread depth they managed to achieve.

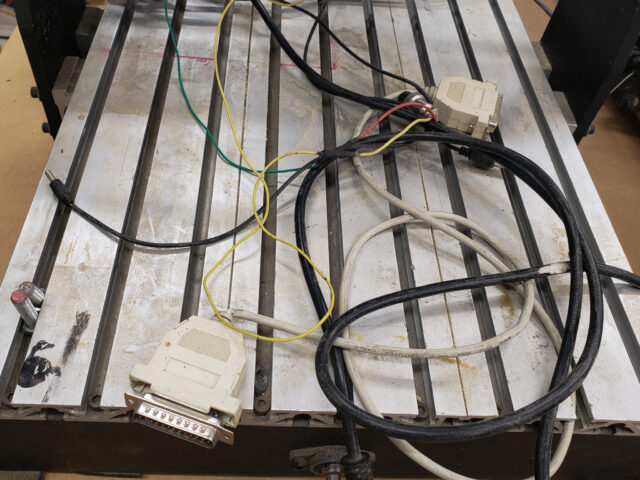

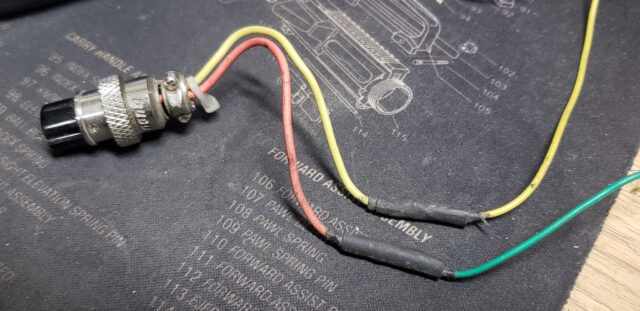

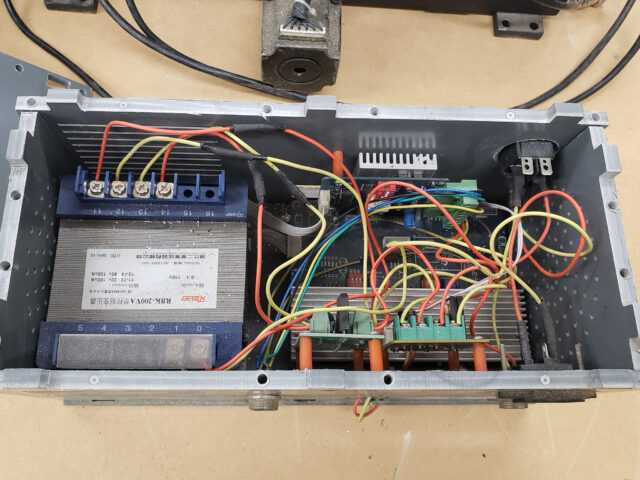

I don’t even want to start on the electronics… It was complete darkness, despair, and utter chaos:

Getting chills yet? That’s exactly how it was everywhere! Including the motor wiring. The original motor wires were clearly too short and were simply cut in half and extended with additional sections using manual twists and corroded black electrical tape. In the best-case scenarios, there was crumbling heat shrink tubing instead of tape. Sometimes, there was both — one layered on top of the other…

Overall, it looked as though a young, inexperienced Chinese DIY-er had been bitten by a seasoned Indian DIY-er. Now doomed, the young DIY-er was condemned to create this. And he would never again produce anything he could show to people without shame. Every one of his projects would inflict unbearable mental anguish, eye bleeding, and chronic facepalming upon others… And then he would start a YouTube channel, and the world would plunge into darkness! I’m telling you the truth here — nothing good comes of this…

Однако, как это ни странно… Станок, в целом, вышел… мнэ… прочным. И, даже, худо-бедно работающим… Вероятно, сработал принцип чётности из “теории ошибок“. Иными причинами я не могу объяснить наблюдаемый феномен.

And yet, strangely enough… The machine was, well, sturdy. And even, to some extent, functional. It worked — barely, but it worked. Probably the principle of even-order errors from the “Theory of Errors”(ru.) came into play here. I can’t think of any other explanation for this phenomenon.

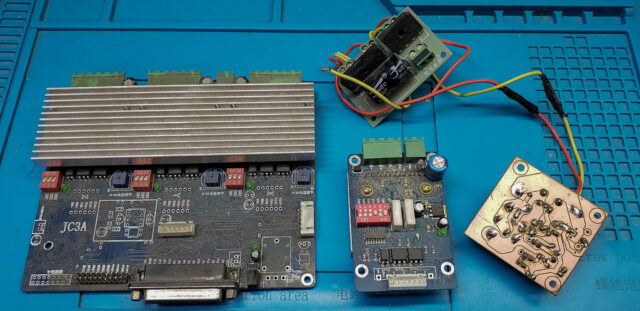

In terms of electronics and control, the machine was just as barebones and pitiful. However, this was likely less due to the creator’s descent into the darkness of cognitive incapacity and more due to the technical limitations of “garage technologies” of that era. It lacked, and had never had, any sort of central controller. Instead, it housed a bulky transformer, a rectifier, a primitive spindle control board, an equally primitive driver board for the stepper motors, and an absolutely prehistoric auxiliary board with a separate driver for the “A” axis:

The spindle control board was homemade — not etched, but CNC-cut. Possibly even on this very machine… I suspect this spindle control functionality was added to the control block in later stages of the machine’s development, once it was able to engrave something basic for itself under manual spindle speed control.

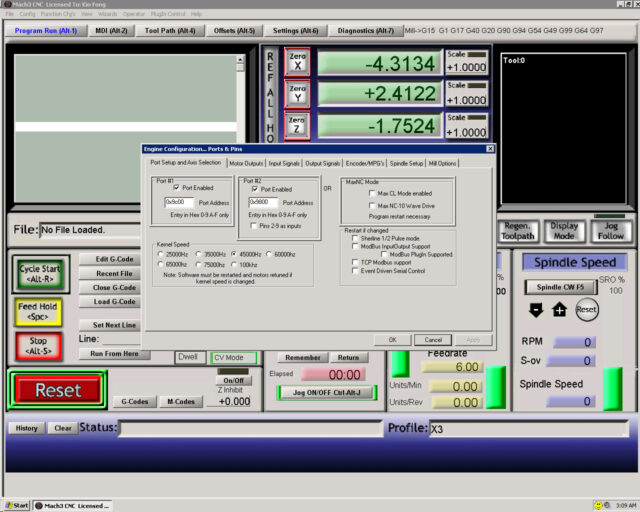

The actual cutting process was controlled by an external computer that sent commands to the driver board via a parallel port. In this particular case, a standard PC-style LPT port.

I only saw all of this working once, but as far as I recall, the computer was running something that looked very much like an ancient version of Mach3, which handled all the operations:

This was yet another reason why, at some point, no one went near this machine anymore. The original computer for the machine had long since disappeared into the depths of the company, and good luck finding a replacement with an LPT port… And even if you did, good luck finding someone who still remembered what it was and what to do with it.

Based on what was discussed above, the plan of action took shape as follows:

- Disassemble everything down to the last screw.

And the screws? Straight to the trash. At least half of them were hopelessly rusted and had no future. - Clean all parts back to their original state.

Wash off all the amateurish grease and strip away the drips of fence-quality paint. - Fix the flaws in the parts.

Straighten out crooked holes, clean or re-tap the threads in the parts, smooth the panel edges, and so on. Basically, a global “file treatment” of sorts. Of course, it won’t be possible to fix everything completely — some “minced meat can’t be turned back into steak.” But at the very least, I’d try to do something about all the mess. And if something proved completely hopeless, I’d likely throw it out and cut a new piece altogether. - Paint it properly.

Anodizing or powder coating would be ideal, of course, but I don’t have the equipment for that yet, and outsourcing it wouldn’t be worth the cost. A decent aerosol job would suffice — but done properly, using good self-etching primer and adhering to basic painting rules. - Reassemble everything.

While at it, replace the motors and spindle with something more suitable. - Install new control electronics.

Design and assemble a new autonomous control unit with its own controller.

Maximum goal: Transform this mediocre hobbyist engraver into a functional hobby-grade CNC milling machine for aluminum, suitable for small parts.

The emerging project was given the name “DOOMSUN E32-FNC“:

A sort of wordplay on the name of a well-known brand of serious machines, which introduced me to the world of CNC machining. Of course, there were others later, but the DOOSAN DNM 4500 was my first “Dusia” — the one that taught me the art of loving robots.

Additionally, considering the unmistakable Chinese origins of this contraption, I find that a playful letter swap in the vein of Adibas (Naik, Pumo, Reebak, etc.) is both culturally appropriate and entirely fair!

As for what “E32” and “FNC” mean — that will become clear later. Though, for those familiar with the subject, it’s probably already obvious…

That’s the story so far. To be continued here.